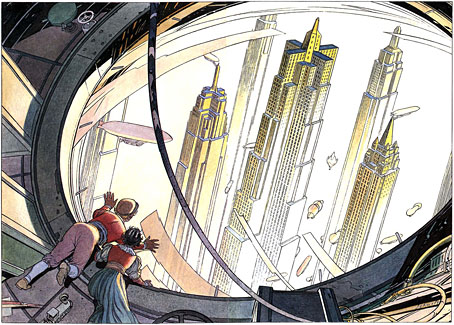

Ferdinand and Hella look down on the skyscrapers of Brüsel.

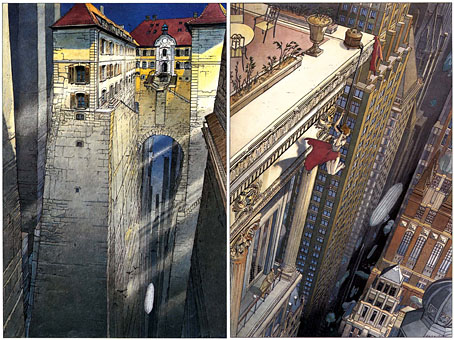

La route d’Armilia (1988) by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters is the next substantial story in the Cités Obscures series after La Tour; there was also a book about transportation in the Obscure World, L’Encyclopédie des transports présents et à venir, published the same year. La route d’Armilia is the book where Schuiten and Peeters’ Jules Verne influence comes to the fore, with the story of a young boy whose name is derived from Verne characters, Ferdinand Robur Hatteras, undertaking an airship journey to Armilia at the Obscure World’s northern pole. As with the earlier L’archivist, this is mainly an excuse for Schuiten to demonstrate his prodigious architectural invention and draughtsmanship, although the story this time is more of a piece. The journey takes us from the city of Mylos—a dismal place of factories, chimneys and smoke, like one of the polluted cities of the early Industrial Revolution—over the cities of Porrentruy, Mukha, Brüsel, Bayreuth, Calvani, Genova and København. Each city is substantially different from the last, and one of the pleasures is seeing what the next stop along the way will be like.

left: the airship passes through the canyon streets of Porrentruy; right: in Brüsel a woman hangs perilously from a ledge. Acrobatics or accident, we never discover which.

The story itself seems rather slight at first, like a Verne tale for children, with the airship crossing desert regions, ocean and ice fields, observing various spectacles along the way. Ferdinand has been given the task of conveying a special code to Armilia which will help correct some machinery there whose operation somehow affects the whole of the Obscure World and whose nature is only revealed near the end. Why a small boy is given this important task is one of a number of conundrums in an ostensibly light narrative which only reveals its truer, darker nature at the conclusion. As with some of the other stories in this series, to say more would be to spoil it for would-be readers. During the journey Ferdinand discovers a girl, Hella, who has managed to stow herself away on the airship, a detail which reinforces the children’s story aspect, as well as the Verne-like narrative.

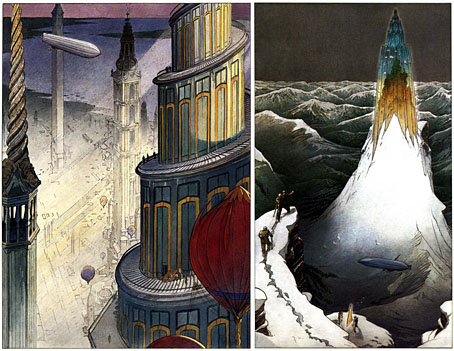

left: the Winsor McCay-like pleasure city of København; right: Mount Glaëver.

Tempting as it is to see this story as a comment on adventure tales, it’s the travelogue quality which is the most important for the artist, and Schuiten fills his pages with stunning views of the cities. Many of these pictures are so beguiling you immediately want to know more about the places they depict, although it’s a shame for me that the city of Calvani (possibly named in homage to Italo Calvino) is only glimpsed through a window. Schuiten has a fondness for greenhouses and terrariums, and it’s no surprise that Laeken in Brussels contains a splendid example of the former. Calvani is a city of elegant greenhouses built to skyscraper proportions, and while we might not enjoy a decent view of the city in this story a whole page is devoted to Mount Glaëver, a peak in a waste of snow and ice whose summit is capped with glass spires enclosing trees and other vegetation. By this point in their books, Schuiten and Peeters resist the temptation to go into too much detail about these enigmatic structures, and they leave them all the more fascinating as a result.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• La Tour by Schuiten & Peeters

• La fièvre d’Urbicande by Schuiten & Peeters

• Les Murailles de Samaris by Schuiten & Peeters

• The art of François Schuiten

• Zeppelin vs. Pterodactyls

• Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux

• The Hetzel editions of Jules Verne

Do you know if these are available in English translations John? Sadly I never picked up any French.

Hi Andrew. All the major books have had English language editions although I’ve not looked to see if they’re still in print. It’s a shame some of the peripheral works–which are just as fascinating at times–haven’t been. One of the reasons for doing this week of posts was to give them a bit more attention in the English-speaking world. Schuiten is very well-known in Europe, as are many other comic creators who you rarely hear about unless you look into the BD world. Moebius has managed to break through the language barrier but even then it was his work doing designs for film which gave him much of the attention.

Off topic but I though you may be interested that The cover of Valerie j Freireich’s novel ‘Becoming Human’

has a version of the Flandrin pose on the cover.

It is a different take upon it,

as he holds a mask.

The image of Copenhagen is especially interesting as those are recognisably based on actual buildings – the Bourse and the Vor Frelser’s Kirke.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/castrovalva/245701525/in/set-72157594261968278/

Thanks Faun, it appears the painting is by John Jude Palencar. I’ve bookmarked it for future reference.

Hi Richard. Yes, a number of these cities have analogues in our world. Schuiten & Peeters’ Brüsel is effectively an alternate Brussels which starts out like the old Brussels then is transformed into a place resembling a pre-glass box Manhattan without any zoning laws. I think the sprawling Obscure World mythos has some explanation for these correlations but I’m not quite sure how they articulate it.